Joey Terrill: Cute and Paste

Ortuzar Projects, New York

January 19 – February 25, 2023

Ortuzar Projects presents Cut and Paste, a survey of collage and related works by JOEY TERRILL from the late 1970s to the present, organized by Rafael Barrientos Martínez. Raised in Highland Park and East Los Angeles, Joey Terrill was part of a small group of Chicano artists who in the 1970s and 80s created works that diverged from traditional Chicano-based imagery and subject matter to include visual representations reflecting his queer lived experiences. Utilizing the existing image culture that surrounded him, Joey Terrill combines personal photographs, found pop cultural imagery, and reproductions of artworks by queer predecessors, including Diane Arbus, Robert Mapplethorpe and Wilhelm von Gloeden, to conjure utopic spaces. Spanning from his earliest explorations to substantial new works, Cut and Paste reveals collage as a foundational element to Joey Terrill’s expanded artistic practice.

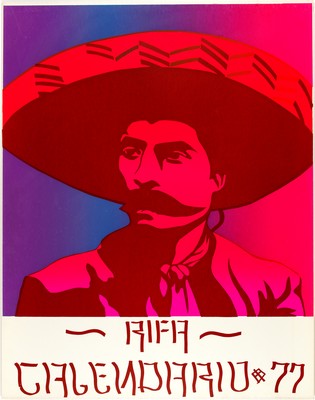

Beginning with abstract collages and silkscreens made while Joey Terrill was an undergraduate at Immaculate Heart College—an art department still heavily influenced by the graphic artist and activist Sister Corita Kent—the exhibition draws out the interconnectivity of illustration, collage, and printmaking in Terrill’s work and their influence upon the characteristically flat style of his early paintings. Like many artists who came of age in the wake of Pop, he found refuge within the fantasies of American image culture–his earliest artworks covering his bedroom walls, which he transformed with a mix of drawings, photographs, and clippings of comic books, film starlets, and music icons. His silkscreens from the mid-1970s–a medium central to the larger Chicano art movement–find him applying a graphic sensibility to not only representations of brown bodies, but queer desire, an impulse he would continue to explore in his episodic Homeboy Beautiful proto-zines from the end of the decade.

At the center of the exhibition is an installation of unframed Xerox, acrylic, and glitter collages–collectively titled It’s Halloween Party Time–originally created as decorations for Halloween parties Joey Terrill threw at his home from 1989 to 1991. These ephemeral objects–not originally conceived as works of art but dutifully preserved–speak to the ways in which art and life are always playfully entangled within Joey Terrill’s practice. The collages combine imagery of grotesque gargoyles and classical sculptures, contemporary nude figures lifted from magazines, Michelangelo’s David, pre-Columbian drawings, and Tom of Finland characters, to create immersive psychedelic environments. Held at the height of the AIDS Crisis, and shortly following his own HIV diagnosis, Joey Terrill’s parties played host to his inner circle of friends and family, including many who were dealing with HIV and AIDS, becoming a safe space for all. Photos from these parties would later be transformed by Joey Terrill into hyper-realistic paintings, a survivor’s account of how humor and mourning, celebration and sickness, commemoration and loss, can be held within the same apartment. These artifacts–alongside photographs and fliers–point towards the lasting power found in creating seemingly ephemeral spaces for the marginalized within a culture characterized by homophobia and racism.

Since the 1990s Joey Terrill has increasingly integrated collage into his art practice. In When I Was Young (1993), the artist paints himself from a photograph lifted from the cover of his second and final issue of Homeboy Beautiful (1979), taken by frequent collaborator Teddy Sandoval, who would die just two years later of AIDS related complications. Depicting the artist wearing a jacket identifying him as an East Angeleno and carrying a lit cartoon bomb, the original photocomic casts Joey Terrill as an undercover reporter exposing a secret network of homeboys/homegirls terrorizing an upper-class Westwood family. As does much of his work, When I Was Young blurs the line between autobiography and fantasy, taking the image of his fictionalized character and recognizing the real-life radicalism of his youth as an artist and activist. In Being Near Him Joey Terrill combines reference to an elementary-school crush and his forever love, actor Richard Gere; in Marky and Billy (both 1993) he overlays two sex symbols, Mark Wahlberg and Billy Baldwin, at that time in the media for homophobic comments, emblazoned in silver glitter with the Spanish translation of “Two guys that I’d let blow me.”

The irony of the image of Wahlberg being sourced from Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine is emphasized in Joey Terrill’s ongoing series of works derived from Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ, which he duplicates with a Warholian vacuity; the repeated martyrdom of Christ a stand-in for the innumerable lives lost to AIDS. As if in repudiation of any criminalization of his queerness, his recent large-scale work, Here I am / Estoy Aquí, presents a baby photo of the artist at the center of a meteor coursing across the sky. This seminal moment finds the infant Joey Terrill surrounded by strings of pearls and details taken from Mapplethorpe photographs of calla lilies and skulls, motifs repeated throughout the artist’s oeuvre that situate himself within the endless cycle of creation and death.

JOEY TERRILL (b. 1955) lives in Los Angeles, California, where he recently retired as the Director of Global Advocacy & Partnerships for the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. Recent solo exhibitions include Self-Portraits, Clones, Icons, and Homages, 1980–1993, Park View/ Paul Soto, Los Angeles (2022); Once Upon a Time: Paintings, 1981–2015, Ortuzar Projects, New York (2021); and Just What is it That Makes Today’s Homos So Different, So Appealing, ONE Gallery, West Hollywood (2013). Recent institutional surveys include the touring Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., organized by Museum of Contemporary Art and ONE Gallery, Los Angeles (2017–2022); ESTAMOS BIEN–La Trienal 20/21, El Museo del Barrio, New York (2020–21); Touching History: Stonewall 50, Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs (2019); Through Positive Eyes, Fowler Museum, University of California, Los Angeles (2019); and ASCO: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2011). His work has recently joined the collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; El Museo del Barrio, New York; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; and Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, among others.

ORTUZAR PROJECTS

9 White Street, New York, NY 10013