The House Was Too Small:

Yoruba Sacred Arts from Africa and Beyond

Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles

October 29, 2023 – June 2, 2024

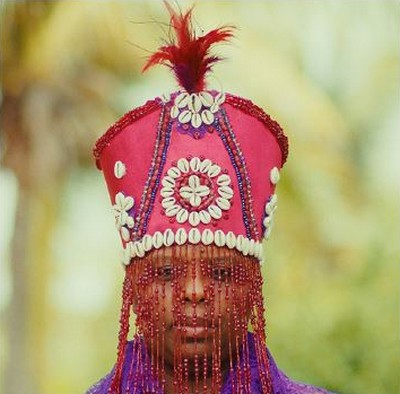

Still image from They Are With Us: Oya in the Grove, 2023

Video directed by Maxwell Addae;

Cinematography by Samudranil Chatterjee

Yoruba peoples, Nigeria, Ogo elegba (dance wand), collected prior to 1958;

Wood, cowrie shells, leather, indigo;

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X64.311

The Fowler Museum at UCLA presents The House Was Too Small: Yoruba Sacred Arts from Africa and Beyond. The exhibition brings together over 100 sacred artworks including carved sculpture, vibrant beadwork, dazzling costumes, and other art forms from Nigeria and Benin and across the Yoruba diaspora in Brazil, Cuba, and the U.S. Together these objects trace continuities and innovations within the religious material culture of the Yoruba Atlantic, a cultural sphere profoundly affected by empire-building, colonialism, the violence of enslavement, international trade networks, and global immigration patterns. In this context, the artworks on view speak to how religions are altered in the diaspora and how individuals are transformed through worship.

Fowler staff worked with a collective of religious practitioners, academics, activists, and artists to develop this exhibition of masterworks from the Fowler collection. Community advisors also authored a selection of labels for personally meaningful objects. These texts offer uncommon insights gleaned from religious training, scholarly research, artistic vision, and lived experience.

For contemporary Ifa practitioner, artist, and abolitionist Patrisse Cullors, Yoruba religiosity is a mode of personal and collective empowerment. This aspect of her faith is realized in Free Us, a multimedia installation within the exhibition. At the exhibition opening October 28 at 5 pm, Cullors will also premiere Ori Whispers, a visually and spiritually dynamic procession from the UCLA Mildred E. Mathias Botanical Garden to the Fowler Museum in a celebration of Black femme Ori strength and power.

The House Was Too Small references a verse from a Yoruba praise poem evoking the mercurial nature of Eshu, a trickster god who features prominently in the pantheon of divinities (orishas or oriśas) of Yoruba religion. An agent of creation and mediation, Eshu is a key protagonist and a guide through the exhibition, appearing at the threshold of each gallery section. Eshu is the element of unpredictability in the world. When you feel you’ve done everything right, you think you’ve fulfilled all the conditions, there is always something you’ve left out and that is the aspect of Eshu that is important. We need to attend to that. So, Eshu is telling us that even when we think we’re perfect, we’ve done everything right, there is something we need to do that hasn’t been done.—Rowland Abiodun, advisor

The exhibition unfolds over five rooms devoted to objects that visualize and enact core spiritual tenets. The penultimate space contains a series of works by artist and abolitionist Patrisse Cullors. Throughout the installation, sacred objects from West African Yoruba religion are juxtaposed with comparable pieces from Afro-Brazilian Candomblé and Afro-Cuban Lucumí. The interplay of historical and contemporary objects illustrates the legacy and expanding reach of Yoruba religion.

Adé (crown) for a devotee of the orichá Ọbàtálá Ògìyan, 1997

Beads, thread, feathers, fabric, wood, shells;

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X95.5.1

Ìlé orí (“house of the head” container), 20th century;

Cowrie shells, leather, rawhide, burlap, cotton cloth, velvet;

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X70.1169A&B

Ori

In traditional Yoruba belief, the head or ori is the site of consciousness, individuality, and spiritual intuition. Two types of objects in the first gallery underscore the importance of both the visible and the inner spiritual heads. Crowns are worn on special occasions by kings and religious practitioners. Beaded veils hang over the eyes, obscuring the wearer’s identity and perhaps shielding their divine nature. Containers frequently encrusted with cowrie shells are known as “house of the head.” They celebrate, protect, and conceal the inner head. Both categories visually reinforce a financial and personal commitment to bettering one’s self.

(Valdete Ribeiro da Silva, b. 1928, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, d. 2014)

Candomblé Oxóssi doll, ca. 1990s;

Cloth, metal, beads, feather;

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X2015.4.21; Gift of Dr. Julio Casoy

Salvador, Bahia Brazil, Candomblé Ibeji (Saints Cosmas and Damian), early 1980s;

Wood, paint, gesso;

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X82.1352; Gift of Mrs. W. Thomas Davis

Orishas

The orisha gallery is the largest, comprised of large tables featuring iconic representations of the paramount deities. Variously described as spirits, personified natural forces, or deified ancestors, orishas are entities that serve as mediators between terrestrial and spiritual realms, and aid people in dealing with everyday realities. Human-like in character and form, orishas are dynamic presences in the lives of worshipers. In some ceremonies, such as an ancestor or egungun masquerade, initiates become vessels for divine embodiment and temporarily personify deities through dress, dance, song, speech, and other actions.

Objects brought together from across the diaspora bear common emblems, materials, strengths, and struggles associated with their orisha. Each table reflects a theological and aesthetic heritage shared across time, continents, and an ocean: beaded staffs for the divine messenger Eshu, dance wands for the thunder god Shango, and fans for the water goddesses Oshun and Yemoja. Ibeji orishas are traditionally represented as carved wood figures memorializing a lost twin child or twins. The Ibeji table thus features wooden figures from Nigeria alongside mass-produced plastic ones now popular throughout the Yoruba Atlantic. Further adaptation in Brazil has associated Ibeji with Cosmas and Damian, twin physicians and Catholic saints. Despite the African connections, this sculpture shows the deities in Western clothing—a cultural mix like many others engendered in Brazilian society, according to advisor Rowland Abiodun.

Ifa

Ifa is the master of todayIfa is the master of tomorrowIfa is the master of the day after tomorrow–Yoruba praise poem

Ifa divination is a central component of Yoruba-based worship in Africa and the Americas. This oracular system offers seekers insights into the circumstances of their lives and provides ethical and moral guidance. Diviners or babalawos memorize an expansive set of oracular texts and use a set of ritual tools to determine the appropriate verses that will address a supplicant’s situation.

The ritual tools in this section include carved and well-used wooden trays, bowls, and long narrow tappers made from wood, metal, or ivory. As part of the Fowler’s engagement with practitioners of Ifa, the museum invited three babalawos who live in Southern California—Oluwo’Nla Irawoifa (Amos Dyson), Olowu Fakolade (Jahsun Edmonds), and Awo Falokun Fasegun (aka Earl White)—to utilize tools from the collection. An in-gallery recording of their ritual sessions helps illustrate key elements of the Ifa divination process.

They Are With Us, 2023

Zihuatanejo, Mexico;

Photograph: Whitney Skauge

Patrisse Cullors, Free Us

Artist, abolitionist, and exhibition advisor Patrisse Cullors created a multipart installation titled Free Us. A longtime practitioner of Ifa, Patrisse Cullors says the installation is for young people looking for spiritual meaning.

I want young people, especially black and brown, to know that there is a tradition beyond the Abrahamaic that may be calling them. Getting to sit on an advisory committee feels historic, powerful. It’s not often that someone occupies roles of Yoruba scholar, artist, initiate, advisor, curator—as a public figure—all of these places that I occupy. It’s a dream come true.—Patrisse Cullors, advisor

In the first room, a silent video short, They Are With Us, (2023), looks at the beauty and enchantment of orishas. The camera cuts between ocean waves and undulating layers of a rich fabric ensemble worn by Patrisse Cullors. She is wearing a crown adorned with cowrie shells and a beaded veil hangs over her eyes.

A second room features UnEarthing Altars (2023), four deconstructed altars dedicated to the orishas Osun, Yemaya, Oya, and Obatala. The simplified altars are comprised of objects from the Fowler collection alongside Patrisse Cullors’ personal offerings, including cloth, shells, kola nut, and elaborate crowns fabricated by Kutula Africana, a Los Angeles-based African fashion and design house.

These pieces unveil the resilience of the orishas and the impact Christian supremacy has had on their legacy. Each orisha is given time and creative space to fulfill their destiny, while also battling a system that refuses to acknowledge their existence. Free Us asks the audience to investigate their relationship to Christian supremacy, anti-African bias, and the mirror each orisha places in front of us as we work to fulfill our destiny.—Patrisse Cullors, advisor

Candomblé Egungun masquerade ensemble

representing an ancestral spirit called Baba Xangô, early 20th century;

Cloth, beads, cowrie shells, mirrors;

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X82.1359; Gift of Mrs. W. Thomas Davis

Egun

Adherents throughout the Yoruba Atlantic honor the dead and recognize ancestors as active participants in the everyday world. While bodies are buried in the ground, spirits or souls enter the afterlife as ancestral forces (egun or egungun) who have the power to intercede in the realm of the living. Beyond facilitating remembrance of the dead, the sacred arts in this final gallery reinforce continuing relationships between the living and the deceased.

Nigerian and Brazilian egungun ensembles in this section are staged as floor-length costumes of multicolor fabrics glittering with small mirrors, cowrie shells, and glass beads. Vibrant cloth strips swirl and flare as the wearer embodies their ancestors at a festival for the dead. In the Yoruba-inspired Cuban Lucumí religious tradition, household altars for the dead include staffs adorned with colorful strips of cloth reminiscent of Yoruba egungun costumes. Featuring candles, photographs, and offerings of fresh water and food, these ritual spaces are reminders that the homes of the living also belong to the ancestors.

Related Programs

This exhibition is accompanied by free programming with artists, curators, and spiritual practitioners. As part of a year-long artist residency, artist and activist Patrisse Cullors will co-curate a series of eight Community Conversations that bring together community organizers, artists, and Ifa practitioners to explore the pan-Yoruba concept of ori (head), understood as one’s inner essence and the site of intuition and potentiality. Events will take place at the Fowler Museum, Crenshaw Dairy Mart and other partner sites throughout the city.

The complete fall schedule will be online October 1 at fowler.edu/programs

The House Was Too Small: Yoruba Sacred Arts from Africa and Beyond was organized by the Fowler Museum and curatorial coordinators Erica P. Jones and Patrick A. Polk. The curatorial advisors on the exhibition are Rowland Abíodun (John C. Newton Professor of Art History and Black Studies, Amherst College); Roberto Conduru (Endowed Distinguished Professor of Art History, SMU); Patrisse Cullors (artist, author, abolitionist); Oluwo’Nla Irawoifa, aka Amos Dyson (Ifa Temple Otura Tukaa); Olowu Fakolade, aka Jahsun Edmonds (Ile Ayo Temple); Awo Falokun Fasegun, aka Earl White (Ile Orunmila Afedefeyo); Ysamur Flores-Peña (associate professor, Otis School of Art); Erica P. Jones (senior curator of African arts and manager of curatorial affairs, Fowler Museum); Elizabeth Pérez (associate professor of religion, UCSB); and Patrick A. Polk (senior curator of Latin American and Caribbean popular arts, Fowler Museum).

FOWLER MUSEUM AT UCLA

308 Charles E Young Dr N, Los Angeles, CA 90095