Rear View

LGDR Gallery, New York

April 18 - June 1, 2023

WORKS BY Francis Bacon, Seth Becker, Fernando Botero, Cecily Brown, Paul Cadmus, Miriam Cahn, Harry Callahan, Jordan Casteel, Francesco Clemente, John Currin, Diane Dal-Pra, Giorgio de Chirico, Edgar Degas, Urs Fischer, Eric Fischl, Jared French, Lucian Freud, Domenico Gnoli, Jenna Gribbon, Barkley L. Hendricks, Anselm Kiefer, Gustav Klimt, René Magritte, Aristide Maillol, Danielle Mckinney, Yoko Ono, Philip Pearlstein, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Larry Rivers, Jenny Saville, Egon Schiele, Pavel Tchelitchew, Mickalene Thomas, Félix Vallotton, Andy Warhol, Carrie Mae Weems, Issy Wood

Étude de fesses, c. 1884

Oil on canvas, 14¹⁵⁄16 × 18⅛ inches (38 × 46 cm)

Photo © Fondation Félix Vallotton, Lausanne

Nude in a Convex Mirror, 2015

Oil on canvas, Diameter: 42 inches (106.7 cm)

Private Collection, Aspen

© John Currin. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

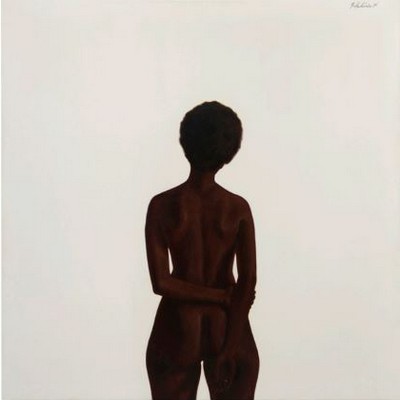

Pat’s Back, 1968

Oil on canvas, 601/4 × 601/4 inches (153 × 153 cm). Private Collection

© Barkley L. Hendricks

Courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks

and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Untitled (Woman Standing Before Commercial Billboard), 2003

Pigment ink print, 20 × 20 inches (50.8 × 50.8 cm). Edition of 5, with 2 AP

© Carrie Mae Weems

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Spanning two floors of LGDR’s landmark Beaux-Arts-style townhouse, Rear View presents a transhistorical selection of over sixty paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and photographs that explore representation of the human figure as seen from behind—an enduring, wide-ranging paradigm that has exerted potent influence upon modern and contemporary artists. In addition to rare twentieth-century masterworks by Félix Vallotton, Edgar Degas, René Magritte, Francis Bacon, Egon Schiele, Paul Cadmus, Aristide Maillol, and others, Rear View brings together seminal works by a diverse group of living artists spanning generations.

Long before the term Rückenfigur was popularized in the nineteenth century by Caspar David Friedrich, painters and sculptors from as far back as antiquity deployed the human figure seen from behind as a conceptual and formal device. Rear View provides a lens onto this specific genre as it pertains to artists’ desire to capture a range of human states and emotions—contemplation, longing, voyeurism, refusal, fetishism, and defiance—while drawing our attention to the act of looking itself and to the viewer’s role in constructing meaning and identity.

Many contemporary artists have engaged the Rückenfigur trope, deliberately harnessing its critical potential. In one of the most compelling examples, Carrie Mae Weems has photographed herself in canonical landscapes and charged historical sites over many years, as a means of addressing complex issues around race, gender, and class, while also subjecting the signature paradigm of Romanticism to radical, politicized revision.

From the idealized bodies celebrated in Hellenistic sculpture to the bathers glimpsed in snapshot-like paintings and drawings by Impressionists and early modernists, images of nude bodies portrayed from behind have been integral to the unfolding story of figuration in the West. Urs Fischer directly quotes the Classical origins of this art historical paradigm in a monumental new candle sculpture made specifically for Rear View. Divine Interventions (2023) reprises one of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Roman marble Three Graces (second century CE), turning the trio of iconic feminine paragons, Aglaia (Beauty), Euphrosyne (Mirth), and Thalia (Abundance), into ephemeral forms cast in wax. Admiring this sculptural group—and in essence joining the Graces—is a wax effigy of Pauline Karpidas, the legendary contemporary art patron who once owned the ancient work that the Met would come to acquire.

The eroticism of “rear view” images emerges not only from the frisson of nudity—the iconography of the human derrière emerges as a whole transhistorical subject onto itself—but from the narrative implication of intimacy between the depicted subject and the artist, the viewer’s fantasizing gaze and the sensuousness of the image on canvas. The trope of the mirror, the ritual of bathing, and the lounging or sleeping body are typical rear view scenarios taken up by artists across the centuries—from Edgar Degas to René Magritte, from Félix Vallotton to Barkley L. Hendricks, through to our present day. Fernando Botero’s painting The Bathroom (1989) features a woman, at once monumental and delicate, gazing at herself in the mirror, wearing only heels and a headband. The figure’s unselfconscious posture suggests she is unaware of the artist, invested only in herself

By contrast, John Currin’s Nude in a Convex Mirror (2015) looks over her shoulder, presumably at the painter who is depicting the curves of her accentuated buttocks—but also at the viewer observing the action. The subject of Paul Cadmus’s c. 1965 crayon drawing Standing Male Nude (NM 48) likewise peeks over his shoulder at the artist and the viewer, but with a loaded glance and flirtatious pose—one foot ever so slightly lifted to reveal its sole—that encode a sexual charge of mutual male gazes into an otherwise classical image. Jared French, who was part of the homosocial circle of artists around Cadmus, are represented in the exhibition by emblematic, dreamlike paintings populated uniquely by idealized male figures. The performative signifiers of masculinity emerge as an important subtheme of Rear View, evident in Giorgio de Chirico’s hyper-stylized Gladiatori (1928), Francis Bacon’s tormented figure in Study for Portrait of John Edwards (1986), and Andy Warhol’s abstracted depiction of a butch man’s hind quarters.

In their foreclosure of a complete picture, turned figures such as Currin’s nude also signal fetishism, another theme explored in Rear View. A number of works in the exhibition illuminate ways in which contemporary painting has absorbed the cinematic motif of the rear view, translating the camerawork of film noir and Hitchcockian thrillers like Rear Window (1954) into paint on canvas or rich black-and-white photographic images. Eric Fischl and Danielle Mckinney, for example, draw upon our collective cinematic imagination in composing their deeply narrative scenes, often populated by mysterious figures shown from the back and seemingly unaware of being observed. By contrast, but with no less enigmatic intensity, Harry Callahan’s mid-century rear-view photographs of his beloved wife, Eleanor, testify to the impact of cinematic vision when personalized to a single, deceptively simple subject.

In this context, another thematic trope of Rear View manifests in the work of Edgar Degas. Second only to his images of ballet dances, Degas’s voyeuristic bathing scenes dominate his vast oeuvre. On view in the exhibition, the artist’s delicate 1889–92 pastel Femme se peignant depicts a young nude female, seen from behind, combing her raven-colored tresses over her head. Degas’s scopophilic gaze focuses on the model’s flowing mane—a visual and psychological effect echoed by Domenico Gnoli’s sumptuous large-scale canvas Curly Red Hair (1969), which lingers over the texture of auburn curls cascading down a woman’s back. Tightly cropped to the subject at hand and denying the identifying details of the figure, this painting reveals Gnoli’s seeming uninterest in the body, except as a support for signifying ornament.

The fragmented, fetishized human body emerged as a loaded trope in art history, according to esteemed feminist scholar Linda Nochlin in her study The Body in Pieces: The Fragment as a Metaphor of Modernity (1994). Spurred by the violence and social upheaval of the French Revolution, Nochlin notes, artists began to systematically deploy radical spatial cropping as well as isolating specific body parts, in order to explore the specific conditions of modern urban life—alienation, desire, suffering, obsession, ambiguous anonymous experiences. Nochlin’s observations find a contemporary echo in Issy Wood’s intimate canvas on view in the exhibition: Health and hotness (2018) shows only the muscular back and bottom of a swimmer framed by her purple bathing suit. Wood’s enigmatic image is also a meditation on the impact of compressed and splitting planes and shapes—a study of the body as an abstraction.

Political refusal and personal irreverence also figure into art historical manifestations of the rear view. Six photographs from Anselm Kiefer’s polemical 1969 series Occupations (Besetzungen) take up this political mantle. In this series, the young artist photographed himself—often shown from behind, mimicking the heroic stance of Friedrich’s Rückenfigur—performing the Nazi salute in front of European monuments and natural sites. Of the series, controversial then as now, art historian Benjamin Buchloh remarked that it is “a real working through of German history. You have to inhabit it to overcome it.”

“String bottoms together in place of signatures for petition of peace.” This is how Yoko Ono described her infamous Film No. 4 (Bottoms) (1966–67)—an 80-minute montage of 365 human bottoms, featuring different genders, races, and body types. Marshaling her conceptual Fluxus rigor and sly humor into a powerful political protest against the Vietnam War, Ono’s provocative film retains its antiwar bite as well as its universalizing humanism today. In the diptych that Francesco Clemente created for Rear View, Gold on Green, Green on Gold (2023), the artist slyly questions the front/back logic that underpins the exhibition as well as the binary thinking that governs so much of Western culture. Using gold leaf and a radically reduced palette, Francesco Clemente portrays ambiguous, gender-indeterminate figures that appear to be engaged in oral sex. The artist muses, “Maybe our mistaken ideas—based on duality, based on ‘us against them’—begin with the fact that we can only see half of what there is. We can only face one direction. We feel incomplete because we can never see completely ourselves. Painting may repair that, offering a vision of totality.”

LGDR

19 East 64 Street, New York, NY 10065