New Terrains:

Contemporary Native American Art

Phillips New York

5 – 23 January 2024

Water Memory, 2015

78 x 78 in.

© Cara Romero / Courtesy of Phillips

Phillips presents the exhibition New Terrains: Contemporary Native American Art, curated by Bruce Hartman, James Trotta-Bono, and Tony Abeyta. The exhibition traces the influences of Modernism, Post-War, and Pop Art, contextualizing the evolution of contemporary Native American art from the mid-20th to early 21st centuries. Showcasing over 60 artists across seven decades, the works reflect the socio-political and artistic periods of their creation. Embracing new ideas and expressions, Native American art continues to evolve, with established, emerging, and under-recognized artists sharing their unique visions of Indigenous artistic identity. Full artist list following.

Each curator have garnered considerable recognition within the museum, artist, or private arenas. They have secured numerous, iconic works by a number of the most significant and highly sought-after contemporary Native American artists to date. Dozens of these artists have recently been featured in one-person or group exhibitions at major museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, The Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, and the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Many of these works have here-to-fore not been publicly exhibited, nor have they been made available to collectors, foundations, or museums for acquisition.

Cara Romero, an outstanding contemporary artist-photographer of Chemehuevi descent, seamlessly intersperses narratives of identity, memory, and the intrinsic relationship between land and people. Currently based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Romero's connection to the Southwest profoundly influences her work. Included in the exhibition is one of her most compelling masterpieces, Water Memory, in a never-before-seen format – a monumental 78” x 78”, edition of 1. This particular artwork encapsulates Romero’s dedicated exploration of cultural imprint and its deep connection to spirituality and the environment. The striking image can be interpreted as a metaphor for immersion in ancestral knowledge and the retention of cultural heritage despite external pressures and societal shifts. Water Memory can be found in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Autry Museum, LACMA, Palm Springs Art Museum, Smithsonian NMAI, The Hood Museum, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Montclair Art Museum, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, and among prominent private collections.

Easy Rider NDN, 2022

59.5” x 78.75” x 7”

© Dana Claxton / Courtesy of Phillips

Dana Claxton (b. 1959) utilizes photography, film, video, and performance to explore colonial histories of the United States & Canada, along with issues of Native representation. Her photographs challenge pervasive stereotypes of Indigenous peoples, often employing humor to contradict popularly held views and depictions. Her works can also evoke inspiration and affirmation, asserting First Nations resilience, survival, and identity. Claxton's commanding, large-scale, backlit color transparency depicts fellow artist Iikaakskitowa against a green background, replete with a buffalo skull and lowrider bicycle. She refers to such works as "fireboxes," rather than "lightboxes."

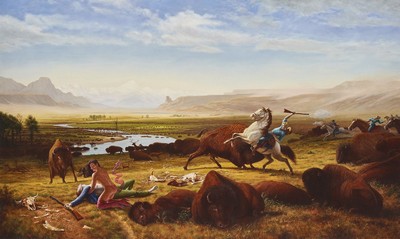

Death of Adonis, 2010

72” x 120”

© Kent Monkman / Courtesy of Phillips

Kent Monkman (b. 1965) is one of the most provocative North American Indigenous artists. He is also one of the most acclaimed and sought after. Revisiting Western genres of art, such as Albert Bierstadt's "The Last of the Buffalo," Monkman sexualizes, decolonizes, and Indigenizes Bierstadt's iconic depiction. In "The Death of Adonis" he inserts a dying, white cowboy cradled by a tearful Miss Chief Eagle Testicle (Monkman's alter ego). Monkman has subverted and reclaimed Bierstadt's mythologized narrative by introducing Indigenous and queer participants. This masterful and monumental painting echoes the exact dimensions of Bierstadt's work.

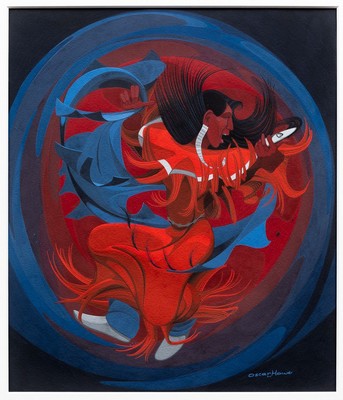

Double Woman (Winyan Nupa), 1962

25” x 21 6/16” (Art) / 39 11/16” x 36 1/16” (Framed)

© The Estate of Oscar Howe / Courtesy of Phillips

Oscar Howe (1915-1983) is among the most highly regarded figures in the cannon of Native American Art. His contribution to the trajectory of stylistic approaches is unparalleled. Double Woman masterfully depicts the female figure suspended in a womb-like bundle of swirling energy. Howe’s work is the most scarce of all his contemporaries and this relatively large, published example is a genuine masterpiece from his most mature period.

Summer Spectrum II, 1958

19” x 50”

© The Estate of George Morrison / Courtesy of Phillips

George Morrison (1919-2000) a Post-War artist, quickly became a regarded figure in New York. He made friendships with and worked alongside Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock and Louise Nevelson. Morrison showed regularly in group shows and had nine solo exhibitions between 1948 and 1960 at Grand Central Moderns Gallery. Summer Spectrum II is an early, seminal example defined by color field variations built from impasto layers of abstraction that predate later delineated horizon landscapes which emerged in his career. Examples of work from this era can be found in the collections of The Whitney, others.

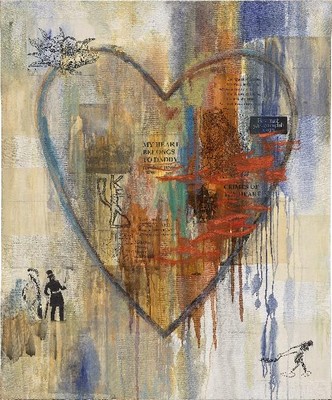

My Heart Belongs to Daddy, 1998

60 x 50 in.

© Jaune Quick-to-See Smith / Courtesy of Phillips

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, is a pioneering force in contemporary Native American art. Quick-to-See Smith’s long and prestigious career has experienced an explosive rise over the past number of years. The artist’s activities have recently led to a highly acclaimed solo retrospective at The Whitney Museum of American Art in NYC this past Spring, 2023. Following this and currently on view, Quick-to-See Smith has curated a landmark exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington DC, the institution’s first show of Contemporary Native American Art in 70 Years. In her major work titled My Heart Belongs to Daddy, the artist excavates the past through painting, mixed media, and collage. My Heart Belongs to Daddy delivers a poignant and thought-provoking critique on cultural appropriation, rather than acculturation, and the commodification of Native American imagery.

Trek (Pleiades), 2014

76 x 118 in.

© Marie Watt / Courtesy of Phillips

Marie Watt, a Seneca artist, infuses her creative endeavors with a strong sense of community, heritage, and storytelling. Raised in the Pacific Northwest, Watt draws from her Indigenous perspective and personal experiences to create art that bridges the gap between tradition and contemporary expression. Her work encompasses a diverse range of mediums, including sculpture, installation, and most notably, large-scale textiles that serve as vessels for collective memory and cultural narratives. Watt's important work from 2014, Trek (Pleiades), hangs as a monumental testament to the power of communal storytelling. Through meticulous stitching, the artist combines disparate elements imbued with historical and symbolic significance. Her use of blankets carries a cultural weight, symbolizing warmth, comfort, and inter-personal bonds within Indigenous communities. Throughout Watt's rise in the art world, marked by numerous accolades and exhibitions in prestigious galleries and museums, she remains deeply rooted in her community. Watt engages in community-driven projects, workshops, and educational initiatives, aiming to amplify Indigenous perspectives and empower the next generation of artists.

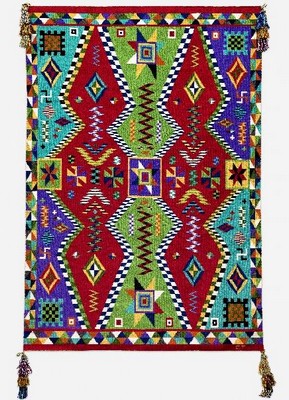

Untitled Red Background Textile, 2022

101.5 x 69.5 in.

© Calvin Toney / Courtesy of Phillips

Born in 1987 in Fort Defiance, Arizona, Navajo artist Calvin Toney currently resides and works near Salina, Arizona. He hails from a long and rich lineage of matriarchal artists. Toney’s grandmother (Beth Bitsuie), mother, and aunt are all renowned weavers. It was with these women that he perfected his weaving skills. The extraordinary Navajo weavings of the late 19th century, most especially weavings employing intensely colorful Germantown yarns, have greatly inspired Toney. A meeting in 2019 with Santa Fe based artist Ken Williams Jr. led to a commission to create a very colorful work and ensured Toney’s subsequent weavings would be a riot of color, fearlessly applied. Toney views his weavings as paintings and his influences are myriad, ranging from Italian Renaissance & Modernist architects, Jackson Pollock, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Faberge, and famed Hopi potter, Nampeyo. His large-scale works, such as those in the exhibition, suit Toney's ambitions to envision and express elaborate, encompassing designs.

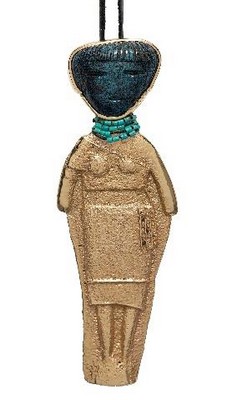

Tufa Cast 14k Gold Hopi Maiden Pendant, 1974

5 x 2 x 1 in.

© Charles Loloma / Courtesy of Phillips

Charles Loloma is one of the most renowned and influential Native American artists in America. Often referred to as The Godfather of contemporary Native American jewelry, his designs were inspired by the iconography of his tribal ceremonialism as well as the cultural origins of the Hopi living in the arid desert of northern Arizona. Loloma's avidly collected pieces are featured in major institutions and were in the prestigious collections of the late Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Frank Lloyd Wright, Lyndon B. Johnson, and the Queen of Denmark, among many others. Loloma’s innovations in the field set the tone for Native jewelry of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. One of his most important and famed creations, an 18K gold and Lander blue turquoise pendant, is included in this exhibition. This turquoise is one of the largest and highest gem-grade stones to come from one of the rarest turquoise mines in the world. The stone was chosen and meticulously hand carved by Loloma to represent the portrait of a sacred Hopi corn maiden. The maiden herself is a single manifestation created by pouring molten gold into a mold made from a Tufa carving, a traditional practice used in Native American jewelry.

On a Slant Village, 2022

102” x 112 ½”

© Teresa Baker / Courtesy of Phillips

Teresa Baker's (b. 1985) desire to circumvent the inherent parameters of traditional canvas led her to discover - quite by accident - bright blue AstroTurf at Home Depot. By her own admission she "was blown away." Baker relates her quirky abstract forms to the vast expanses of the Northern Plains, remembered from her youth. She now conjoins the use of synthetic materials with organic ones (buckskin, willow buffalo hide, and parfleche). Baker’s enigmatic constructions are uncannily alluring, visceral, and compelling.

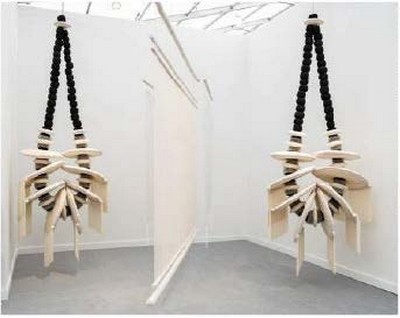

jaatloh4Ye’iitsoh [7-8], 2022

132” x 36” x 24”

© Eric Paul Riege / Courtesy of Phillips

Eric Paul Riege (b. 1994) draws inspiration from the generations of Navajo weavers in his family. His works address his philosophies of spirituality, harmony, and interconnectedness. Riege's woven sculptures, wearable art, and durational performances create immersive spaces, as well as intimate objects rendered monumental. Many of his oversized soft sculptures reference Native American/Navajo jewelry. Riege's giant earrings, "jaatloh4Ye'iitsoh(7-8)," are simultaneously unnerving, endearing, and challenging. He strives for his work to "exist as a kind of forest, the objects acting like trees that are swaying."

Sitting Indian, 1972

80” x 68”

© The Estate of Fritz Scholder / Courtesy of Phillips

Fritz Scholder (1937-2005), one of the most critical Native American artists of the 20th Century, was a breakthrough force that stood apart from all of his peers as someone who could bring the concept of “real” Indian to contemporary art dialogue. Scholder's work is frightfully compelling. Through his manipulation of the dichotomy between tradition and modernism, Scholder wrought a completely unique artistic voice and vision. To this day, it remains fresh, bold, and cutting edge. His most iconic works deal with dominant Colonial misunderstandings of cultural identity and Sitting Indian is a monumental and iconic from this highly accomplished period.

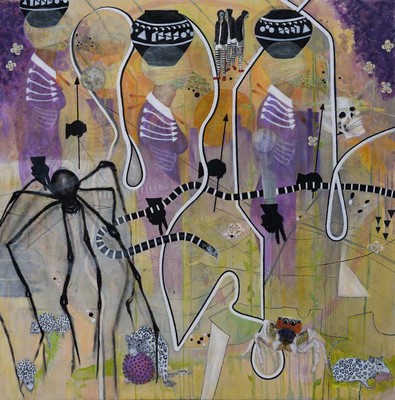

The Web of Transformation, 2021-2022

72” x 72”

© Geralyn Montano / Courtesy of Phillips

Geralyn Montano (b. 1961) is inspired by personal experiences relating to cultural and feminist themes. She expresses powerful, deeply emotional ideas and confronts controversial and taboo subjects. The Web of Transformation reflects upon the dark days of the Covid-19 pandemic. Montano’s work is intended as commentary on complicated social, environmental, and political issues - particularly those impacting the indigenous community. Her disparate images question how we are interconnected and interdependent on each other and on nature.

Ascension, 2022

72.5 x 52 7.8 x 53 in.

Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Nicholas Galanin is a conceptual artist working from his studio in Sitka, Alaska. His practice traverses a vast spectrum of medias which investigate and converse on ideas of land, identity, repatriation, cultural authenticity, extinction, technology, and the often-conflicting interactions and perceptions between Native and Anglo cultures. Galanin’s work challenges institutions to reconsider their role in telling Indigenous people’s stories. Galanin is one of the most esteemed Native American artists working today. His work has been prominently exhibited in many museums and private collections, such as the National Gallery of Canada, SITE Santa Fe, the Denver Art Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Gallery in Washington, DC. Ascension, a decorated ladder with wings blending consumer visuals and Indigenous symbols, embodies diverse interpretations within its form. According to the artist, “to ascend means to rise to a position of importance and references the Christian belief in Christ’s ascension to heaven after resurrection. In this light, the sculpture is a kind of lens for considering the ways Indigenous culture is made into a tool for climbing, particularly by those who do not belong to it.”

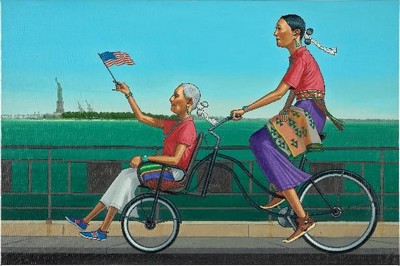

Liberty, 2023

24 x 36 in.

© Craig George / Courtesy of Phillips

Craig George frames his narratives in the context of urbanity, giving voice to questions about assimilation, colonization, and a persistent survival that evidences his connection to rich tribal sources. George grew up on the Navajo reservation, however, due to the Navajo Indian Relocation Act of 1956, his family was relocated to Los Angeles. During the summer he would reconnect with his homelands and the perspectives of a traditional life. Many of George’s paintings reflect his relationship to specific neighborhoods in Los Angeles where he depicts a place of urbanity with the soundtrack of hip hop, gentrification, and downtown LA’s colorful urban edge - streets marked with the vernacular of territorial graffiti. His figures, often on bicycles, are always moving, as if enroute to ceremony, dressed in customary attire. Navajos, Apaches, and Pueblos alike were a part of his community. He has sought a connection to their homelands, while living amidst the chaos of a never-ending urban sprawl. In the words of the artist, "I merge my worlds into one place, one where I am at peace with my beliefs and my environment. Home is a place where you take your beliefs to, so they will always be there.” Several of his works on view were created for this exhibition - his first New York showing.

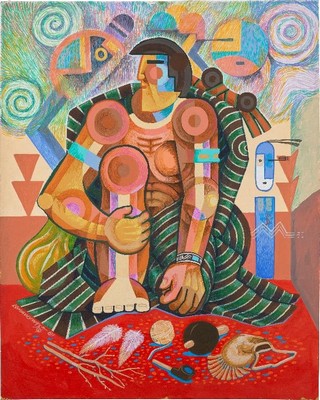

Meditation, 1989

19.5 x 15.5 in.

© Michael Kabotie / Courtesy of Phillips

Michael Kabotie was a Hopi painter, silversmith, sculptor, and poet. His father, Fred Kabotie, was also a nationally renowned artist. Kabotie grew up in the village of Shongopovi, Arizona, however, when the Hopi reservation high school closed, he moved and graduated from Haskell Indian School, Lawrence, Kansas, in 1961. In 1967, Kabotie was initiated into the Hopi Wuwutsim Society. During this ceremony, he was given the Hopi name Lomawywesa (Walking in Harmony) with which he subsequently signed his work. Kabotie joined with four other Hopi artists in the early 1970s to found a group called Artist Hopid, dedicated to new translations of Hopi art forms and serving as cultural emissaries to the world at large. He lectured and exhibited widely both in America and abroad. Kabotie’s dynamically composed and richly hued paintings evidence his fascination with imagery derived from Hopi kiva murals, basketry motifs, and abstract, contemporary designs. Meditation beautifully encapsulates Kabotie's seamless integration of abstract and representational elements. A highly stylized figure, seemingly cubistic, is merged with traditional Hopi motifs and patterns. Representative of his most distinctive and visually compelling works, Kabotie’s use of color is unabashed, imaginative, and expressive.

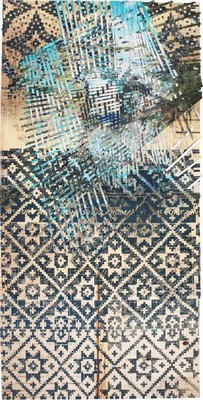

Hinushi 9, 2023

40 x 80 in.

© Sarah Sense / Courtesy of Phillips

Sarah Sense (Chitimacha & Choctaw) is from Sacramento, California and received her BFA from California State University Chico and her MFA from Parsons the New School for Design in New York. Her early works, executed through photo-weaving (employing traditional family basket making techniques and patterns), are based on Chitimacha landscapes in Louisiana and Hollywood’s interpretations of Native North America. Subsequently, her work has reflected her extensive research, residencies, and travel in South America, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, and Ireland. The artworks in Sense's series, Hinushi, are composed from a series of landscape photographs of ancestral homelands integrated with colonial maps of the Mississippi River, Gulf of Mexico, and Choctaw allotment land. Following removal from their ancestral land, Choctaws endured an arduous and deadly walk to "Indian Territory" – now known as Oklahoma. Entwined in the artworks are maps from Oil News (1920) with Broken Bow, Oklahoma landscapes. Choctaw basket patterns are woven through these maps and images, joining the land with the colonial maps as an act of reclamation. As stated by Sense, "Cutting the paper into strips and opening them, moving them apart to create spaces for differing interpretations and re-inserting indigenous patterns from the very same locations where the ancestors were removed, taken and killed, is a process of decolonizing." Visually and conceptually compelling, they are the expression of an intensely personal, yet universally applicable, journey of discovery, revelation, and reconciliation.

FULL ARTIST LIST

Alex Janvier

Diane O'Leary

Jeffrey Gibson

Patrick Swazo Hinds

Allan Houser

Diego Romero

Jerry Ingram

Pop Chalee

Anita Fields

Edgar Heap of Birds

Joe Herrera

Preston Singletary

Anna Tsouhlarakis

Emma Lewis

Julie Buffalohead

Rabbett Before Horses Strickland

Arthur Amiotte

Emmi Whitehorse

Kay WalkingStick

Rhonda Holy Bear

Billy Soza War Soldier

Eric Paul Riege

Ken Williams

Richard Glazer Danay

Brad Kahlhamer

Esteban Cabeza de Baca

Kent Monkman

Sarah Sense

Calvin Toney

Fritz Scholder

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun

Starr Hardridge

Cannupa Hanska Luger

George Alexander

Margaret Jacobs

TC Cannon

Cara Romero

George Morrison

Marie Watt

Teresa Baker

Carol Emarthle Douglas

Geralyn Montano

McKee Platero

Tony Abeyta

Caroline Monnet

Grey Cohoe

Michael Kabotie

Tony Da

Charles Loloma

Harry Fonseca

Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas

Valjean Hessing

Craig George

Helen Hardin

Narciso Abeyta

Virgil Ortiz

Dana Claxton

James Lavadour

Nicholas Galanin

Yatika Starr Fields

David Bradley

Jamie Okuma

Norman Akers

Dempsey Bob

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Oscar Howe

PHILLIPS NEW YORK

432 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022